The Literary Art of Raja Rao

"There is no village in India, however mean, that has not a rich sthala-purana, or legendary history, of its own. Some god or godlike hero has passed by the village--Rama might have rested under this pipal-tree, Sita might have dried her clothes, after her bath, on this yellow stone, or the Mahatma himself, on one of his many pilgrimages through the country, might have slept in this hut, the low one, by the village gate. In this way the past mingles with the present, and the gods mingle with men to make the repertory of your grandmother always bright. ...

We, in India, think quickly, we talk quickly, and when we move, we move quickly. There must be something in the sun of India that makes us rush and tumble and run on. And our paths are paths interminable. The Mahabharata has 214,778 verses and the Ramayana 48,000. The Puranas are endless and innumerable. We have neither punctuation nor the treacherous 'ats' and 'ons' to bother us--we tell one interminable tale. Episode follows episode, and when our thoughts stop our breath stops, and we move on to another thought. This was and still is the ordinary style of our story-telling. I have tried to follow it myself in this story.

It may have been told of an evening, when as the dusk falls, and through the sudden quiet, lights leap up in house after house, and stretching her bedding on the veranda, a grandmother might have told you, newcomer, the sad tale of her village."

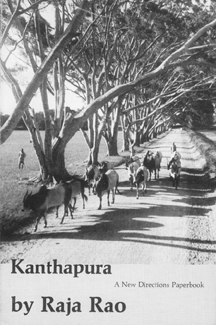

--excerpted from Raja Rao's introduction to his first novel, Kanthapura, 1937

"The whole oeuvre of Raja Rao is notable for seriousness of purpose, profundity of thought, a flair for vivid presentation of detail and a distinctive and vigorous English prose. ... In fact, Raja Rao's own style is as yet the best example of this kind of distinctive expression in Indian fiction in English.

Rao is one of the most innovative novelists now writing. Departing boldly from the European tradition of the novel he has indigenized it in the process of assimilating material from the Indian literary tradition. He explores the metaphysical basis of writing itself, and of the world, through his works of fiction. His concern is with the human condition rather than with a particular nation or people. Writing to him is sadhana, a form of spiritual growth. That is why he can say that he would go on writing even if he were alone in the world. In appropriating for fiction the domain of metaphysics, Raja Rao has enlarged the potential of the very genre."

--excerpted from U.R. Anantha Murthy's essay, "Raja Rao" in Word as Mantra, Robert L. Hardgrave, ed., Delhi, Katha, 1998.

"Raja Rao has received due acclaim for his innovative genetic contributions to Indian English writing, for being indeed a founding author of this branch of modern literature, and for pioneering a distinctive Indian subgenre of fiction usually referred to as the metaphysical novel. This type of novel, anticipated and conceived in some of Rao's short stories, was of course presented to us in 1960 as The Serpent and the Rope. The experimental impulses in Rao's oeuvre are so rich, diverse, yet (let us be frank) at times obscure and esoteric as to defy ready definition and convenient classification. Still, even initial responses to Rao's work recognize his literary experimentation with language, idiom, symbolism, cross-cultural narratology, autobiography, philosophy, history, romance, Pilgrim's Progress archetypes, and representation of character and human relationships, to name some of the main and more obvious areas of his creativity."

--excerpted from S.C. Harrex's essay, "Typology and Modes: Raja Rao's Experiments in Short Story," in World Literature Today, Autumn 1988

Young Moorthy, back from the city with "new ideas," cuts across the ancient barriers of caste to unite the villagers in non-violent action--which is met with violence by landlords and police. The dramatic tale unfolds in a poetic, almost mythical style which conveys as never before the rich textures of Indian rural life. The narrator is an old woman, imbued with the legendary history of the region, who knows the past of all the characters and comments on their actions with sharp-eyed wisdom. Her narrative, and the way she tells it, evokes the spirit of India's traditional folk-epics. (publisher's note)

"E.M. Forster considered Kanthapura to be the best novel ever written in English by an Indian. Not the least of its merits is the picture it gives of life in one of the innumerable villages that are the repositories of India's ancient but living culture. In vivid detail, Rao describes the daily activities, the religious observances and the social structure of the community, and he brings to life in his pages a dozen or more unforgettable individual villagers. The novel is political on a suprerficial level, in that it chronicles a revolt against an exploitative plantation manager and the police who support him. But more profoundly, it traces the origins of the activities of the Congress party. One of the young men of the village, while away, undergoes a mystical conversion to Satyagraha, and returns to incite his fellow villagers to civil disobedience. He arouses in them not only a sense of social wrong but, more importantly, a religious fervour which proves to be the true source of their strength against the oppressors."

--excerpted from U.R. Anantha Murthy's essay, "Raja Rao" in Word as Mantra, Robert L. Hardgrave, ed., Delhi, Katha, 1998.

The Serpent and the Rope (symbols of illusion and reality in Indian tradition) gives the full implication of the meeting of East and West on the most intimate plane by Rama, a young Indian, and his story moves through India, France, and England at the time of the Queen's Coronation. Madeleine, his French wife, seeks a human answer to her problems, which she ultimately finds in a personal equation of Catholicism and Buddhism; for Rama a solution is not so easy, but eventually he realizes that he must take the final leap into reality, and search for a Teacher, his Guru. (publisher's note)

"Semi-autobiographical, The Serpent and the Rope records the disintegration of a marriage, mainly on philosophical grounds, of a very scholarly Indian Brahmin and a French woman professor. The union flounders on the incompatibility of the Brahmin's Vedantic conviction that 'Reality is my Self' and the wife's Western belief--even though she has become a Buddhist--that the evidence of our senses is based on an objective reality outside ourselves. 'The world is either unreal or real--the serpent or the rope,' the Brahmin assures his wife. 'There is no in-between-the-two...' The intellectual demands that Raja Rao, roaming at large through world history and among the religions, philosophies, and literatures of Europe and Asia, makes upon his readers are unequalled in any modern novel since Thomas Mann's The Magic Mountain.

--excerpted from U.R. Anantha Murthy's essay, "Raja Rao" in Word as Mantra, Robert L. Hardgrave, ed., Delhi, Katha, 1998.

Wittily, with extraordinary common sense and gusto, Govindan Nair--an astute, down-to-earth philosopher and clerk--tackles the problems of routine living. His refreshing and unorthodox conclusions continally panic Ramakrishna Pai, Nair's friend, neighbor, and narrator of the story. This is a gentle, almost teasing fable, plain-spoken and humorous. Descriptions of daily concerns are compassionate and evocative. The raw texture of Indian life is woven into the tale of two friends whose own lives have the simplicity of joy and the unaffected universality of Shakespeare, who India has wisely made her own. (publisher's note)

"The Cat and Shakespeare is much shorter and lighter in tone [than The Serpent and the Rope], though scarcely less metaphysical. The subject of its probings is the problem of individual destiny, and the solution is conveyed through an odd analogy offered by a government clerk: 'Learn the way of the kitten. Then you are saved. Allow the mother cat, sir, to carry you.' Raja Rao here exploits the Vedantic idea of the world being a play--lila--of the Absolute, and the result is a hilarious comedy that does not even spare Shakespeare and his language."

--excerpted from U.R. Anantha Murthy's essay, "Raja Rao" in Word as Mantra, Robert L. Hardgrave, ed., Delhi, Katha, 1998.

The Chessmaster and His Moves functions, all at once, at several different levels. At one level it is the story of an impossible love between Sivarama Sastri, an Indian mathematician working in Paris and a married woman which can only end in sorrow and despair. To come to terms with its impossibility, the protagonists turn inward in their search for answer and meaning, transforming the book into a metaphysical exploration. Amidst this search, each and every act, big or seemingly small, gets imbued with special meaning. Sastri's love for the French actress, Suzanne Chantereux, or her beguiling, effervescent compatriot Mireille, for instance, serve to underline the differences between the East and West; while the latter seek happiness in the world, Sastri is looking for freedom from the world itself.

The Chessmaster is rich: in language, plot, in complexity, too, it is rich. And rich in locale and in its large cast of memorable characters--Indian, European, African, and Jewish. By turns tender, tragic, sensuous--or filled with laughter and delight--the book nevertheless remains utterly serious, concerned with the author's abstract search for the Absolute. Grand in sweep and range, the story moves from France to London, and on to the Himalayas and Bengal and contains, perhaps for the first time ever in a literary work, a dialogue between a Brahmin and a Rabbi: an exploration of reasons for the Holocaust and an attempt to expiate it. (publisher's note)

"The Chessmaster and His Moves is firmly rooted in the Indian metaphysical tradition that it seeks to illuminate in the form of an epic novel encompassing three countries--India, England and France--besides the fourth one, of the human mind. Structured as a bhashya on the esoteric knowledge of India often expressed in the terse, aphoristic style charactersitic of such commentaries, totally indigenous in the narrative pattern that collapses a number of stories as in Bana's Kadambari or the Vikramaditya Tales, The Chessmaster and His Moves reveals the great Upanishadic truth of tat twam asi from the metaphysical position of Advaita Vedanta. The characters here seem to comprise a scale of spiritual awareness in terms of deliverance."

--excerpted from U.R. Anantha Murthy's essay, "Raja Rao" in Word as Mantra, Robert L. Hardgrave, ed., Delhi, Katha, 1998.

In this book Raja Rao explores the play of life as it unfolds in Benares, the cherished ultimate destination of millions of Indians, the holy city to die in. And so it is that to the Ganga ghats in Benares come rajahs and princes from Bengal; beggars; Katiawari merchants; courtesans; crooks; simpletons and charlatans--seeking meaning in life, or redemption in death. No less varied are the creatures of Benares themselves: the gentle, brahmchari Madhoba and his Mohini--a feminine presence, 'something more than a goddess, a woman;' Bhim, the sage parrot; the Brahmini cow Jhaveri Bai peering at her reflection in the Ganga waters; bounteous concubines like Nanna; hard-swearing, mantra-chanting sadhus laughing at the foibles of others. (publisher's note)

"These stories are so structured that the whole book should be read as one single novel. All persons and places are not true--but real." --from Raja Rao's introduction, 1988

"India is not a country," writes Raja Rao, "it is a perspective." This book explores the perspective which he calls India--its metaphysic, the philosophical underpinning that sets India apart, uniquely distinguishes its civilization.

Through fable and real-life encounters, descriptions of journeys and events, or in discussions with contemporaries, Raja Rao's quest is unceasing and single-focused: how this perspective alone can give meaning to man's daily action. He draws on a wide range of sources, including the Vedas, Upanishads, teachings of Sankara, the writings of Bhartrihari, and the poetry of Valery and Mallarme. There are essays that describe his meetings with Gandhi and Nehru, so too with Forster and Malraux, westerners who drew close to India.

This book grew over several decades during which Raja Rao created his unique body of fiction. The Meaning of India paints and details the essential metaphysical backdrop of his acclaimed writing. Written in rhythmic, sparkling style which Raja Rao has made his own since Kanthapura, both simple and eclectic, expansive and precise, this book holds that India's civilization and meaning can only be known by understanding the truth about one's own existence and that of the world.

This meaning, as Raja Rao puts it, "is not a question of success or defeat, but abolition of contradiction, of duality." (publisher's note)

HOME HIS LIFE HIS WORK

HIS PHILOSOPHY HIS ART TRIBUTE RAJA RAO PROJECT

BOOKSTORE CONTACT US LINKS